A wonderfully evocative (if verbose) piece by Oliver Wendell Holmes, père, as he sought fils amongst the wounded of South Mountain. One of the un(der)written facets of the war are how many parents, sibilings and loved ones descended upon battlefields in the days, weeks following a battle, searching for their boys. Holmes eventually found his alive and well, and his descriptions flow perfectly from that tight knot of uncertainty and foreboding to sweet, effusive relief, with the sobering reminder that many others’ stories did not end as happily.

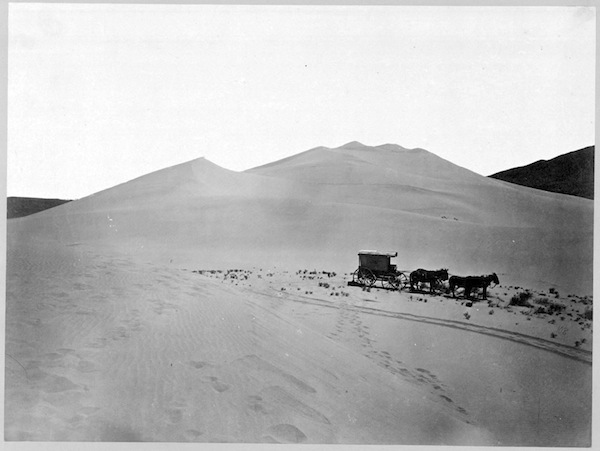

And now, as we emerged from Frederick, we struck at once upon the trail from the great battle-field. The road was filled with straggling and wounded soldiers. All who could travel on foot,–multitudes with slight wounds of the upper limbs, the head, or face,–were told to take up their beds,–alight burden or none at all,–and walk. Just as the battle-field sucks everything into its red vortex for the conflict, so does it drive everything off in long, diverging rays after the fierce centripetal forces have met and neutralized each other. For more than a week there had been sharp fighting all along this road. Through the streets of Frederick, through Crampton’s Gap, over South Mountain, sweeping at last the hills and the woods that skirt the windings of the Antietam, the long battle had travelled, like one of those tornadoes which tear their path through our fields and villages. The slain of higher condition, “embalmed” and iron-cased, were sliding off on the railways to their far homes; the dead of the rank and file were being gathered up and committed hastily to the earth; the gravely wounded were cared for hard by the scene of conflict, or pushed a little way along to the neighboring villages; while those who could walk were meeting us, as I have said, at every step in the road. It was a pitiable sight, truly pitiable, yet so vast, so far beyond the possibility of relief, that many single sorrows of small dimensions have wrought upon my feelings more than the sight of this great caravan of maimed pilgrims. The companionship of so many seemed to make a joint-stock of their suffering; it was next to impossible to individualize it, and so bring it home, as one can do with a single broken limb or aching wound. Then they were all of the male sex, and in the freshness or the prime of their strength. Though they tramped so wearily along, yet there was rest and kind nursing in store for them. These wounds they bore would be the medals they would show their children and grandchildren by and by. Who would not rather wear his decorations beneath his uniform than on it?

MY HUNT AFTER “THE CAPTAIN” (Essay in Pages From an Old Volume of Life).