I’m proclaiming this week Emancipation Proclamation week here at the CWP. It’s just too big an anniversary for all the mainstream news outlets to ignore, and they’re proffering some fantastic articles I want to share.

The video here lets you see what the Proclamation actually looks like. As the article says, it’s wonderfully, revealingly banal. I love the ribbons and the affixed seal. As a history fanatic with ridiculously sweaty hands, though, I was sent to new depths of stress-sweats watching the curator touching the paper with her bare hands. All the while talking about methods to keep the acid out of the paper.

But what’s pretty amazing about the juxtaposition here — the document that bears the phrase “forever free,” folded and be-ribboned — is how eloquently it expresses technological frailty as a symptom of human frailty. The Proclamation wasn’t written double-sided because people couldn’t afford paper back then, or because they thought paper was more enduring than parchment, or because, indeed, they made any strategic decision at all to write the Proclamation the way they did; it was written that way because that’s just how things were done at that particular moment in our history. I asked Archives representatives about the double-sided nature of the Proclamation; they replied that “writing on both sides of the document was the convention of the time. It was written on a folded folio so that they could have four writing surfaces.” That’s it: Folio was the convention, so that’s what they did. (The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation — the document that announced the Emancipation would take effect on January 1, 1863 — is written in the same format.) Technology isn’t just about tools; it’s about the assumptions and conventions that inform our use of those tools. And in the America of 1863, matters of national business were conducted with folded paper and punches and ribbons. Not for reasons that were transcendent, but for reasons that were wonderfully, revealingly banal.

via The Emancipation Proclamation Was Written Double-Sided – Megan Garber – The Atlantic.

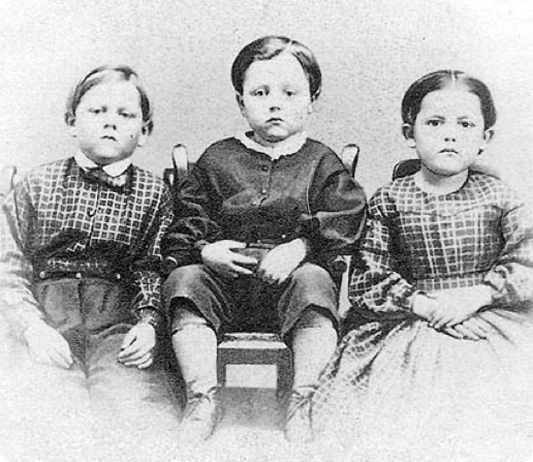

On October 19th, I mentioned the anniversary of Whose Father Was He?, the Philadelphia Inquirer’s story about Amos Humiston, whose body was found on the Gettysburg body clutching a photo of his children. Today is the anniversary of Mrs. Humiston’s response to the Inquirer, and for those interested in reading more about the tragedy of Amos Humiston and his children, I present the five-part history written by documentary filmmaker Errol Morris for the New York Times:

On October 19th, I mentioned the anniversary of Whose Father Was He?, the Philadelphia Inquirer’s story about Amos Humiston, whose body was found on the Gettysburg body clutching a photo of his children. Today is the anniversary of Mrs. Humiston’s response to the Inquirer, and for those interested in reading more about the tragedy of Amos Humiston and his children, I present the five-part history written by documentary filmmaker Errol Morris for the New York Times: